*The history of Archibald Buster (1802-1894) was compiled many years ago by Lottie Buster, a daughter of Claudius Green Buster, and grand-daughter of Archibald. Many, many thanks must go to her for writing down these facts about Archibald’s life, with which we would otherwise be without and they would be lost in the pages of past history. (originally shared on Ancestry.com Feb. 13, 2008)

| Nolichucky River Valley |

Archibald, one of nine children born to Claudius & Isabella (Woods) Buster, was born on March 22, 1802 in Greene Co. Tennessee. He was born along Nolichucky River, near Greeneville, where his parents had settled in 1789. Archibald grew up on the new frontier of eastern Tennessee and on August 18, 1829 was united in marriage to Elizabeth Black Henderson, daughter of David & Isabel (Libby) Black Henderson. Elizabeth wad born in Kentucky on January 30, 1809. Archibald and Elizabeth lived in Tenn. About 5 or 6 years after their marriage, three children were born to them in Tenn. Before they migrated west to Missouri and were pioneer settlers in this vast new land. Eight more children were born in Missouri. Three of their children died in infancy. Martha Ann, their first child, was born in Greene Co. Tenn., on June 13, 1830. Samuel on Feb. 29, 1832. On March 8, 1832 they were deeply sorrowed by the death of Martha Ann. She was buried in Tennessee. On March 10, 1834, their third child, Mary Jane was born.

In or about 1835, Archibald moved his family west by covered wagon to Missouri. Their next child, Sarah Elizabeth, was born in Johnson Co. Missouri on Feb. 20, 1836. On Oct. 11, 1838, William Marion was born. On March 20, 1841 Paulina was born. On Sept. 4, 1843 they became the proud parents of twins when James and Margaret E. were born. But their joy was not to last, for on June 25, 1844 James passed away aged 9 months and twenty-one days. On Nov. 30, 1846 their home was again brightened by the birth of Claudius Green. Then on June 26, 1847 sorrow again struck their home with the death of the remaining twin, Margaret E. age 3 years nine months and twenty-one days. This the third child they had laid to rest. On April 24, 1849 David Elzy was born and five years later, on March 26, 1854, Eliza was born.

|

| The Platte Purchase region (highlighted in red) |

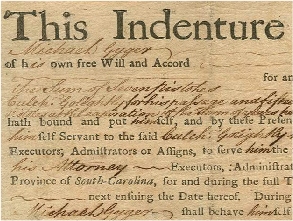

When Archibald and Elizabeth first reached Missouri they seemed to have lived in several different places, always searching for better land and a better place to raise their family. They lived at various times in Saline, Petis, Platte, Johnson and Atchison counties. Sometime during these years in Missouri, we know not the date, they moved south into Texas, but their stay was of short duration. They lost all their cattle with Texas Fever. Grand-mother, Elizabeth, traded a feather bed for a yoke of oxen and they moved back to Missouri. They seemed to have settled, first in Platte County, later moving to Atchison County where they entered on 180 acres of Government land at $1.25 per acre. This was before the Homestead Act was passed. They came into what was then called, “The Platte Purchase” seeking cheap land, but land also rich in natural resources.

Missouri was considered way out west in those days and life was rough. They suffered many hardships in those pioneer days. All water had to be carried from a spring or creek. They had to cut and split rails with which to fence their land and protect it from marauding animals. They lived in log or dirt houses which they most often had to build for themselves. They built fireplaces along one inside wall of these houses where their winter cooking was done. These fireplaces were also used for heating their homes, and often for light to do their evenings work. In the summertime they would build what was called Dutch-ovens out in the yard and under the trees, here their summer cooking was done. Their cooking utensils consisted of various pots and pans and a big deep skillet which had a lid two inches wider than the skillet and a long handle. This they used for making corn-bread, etc. They would place the batter in the skillet, bury it in the live coals, and let it bake. It was said that daughters Sarah Elizabeth and Mary Jane both owned cook stoves long before their mother did. People, at that time thought they were living too fast and extravagant to last long with such modern conveniences.

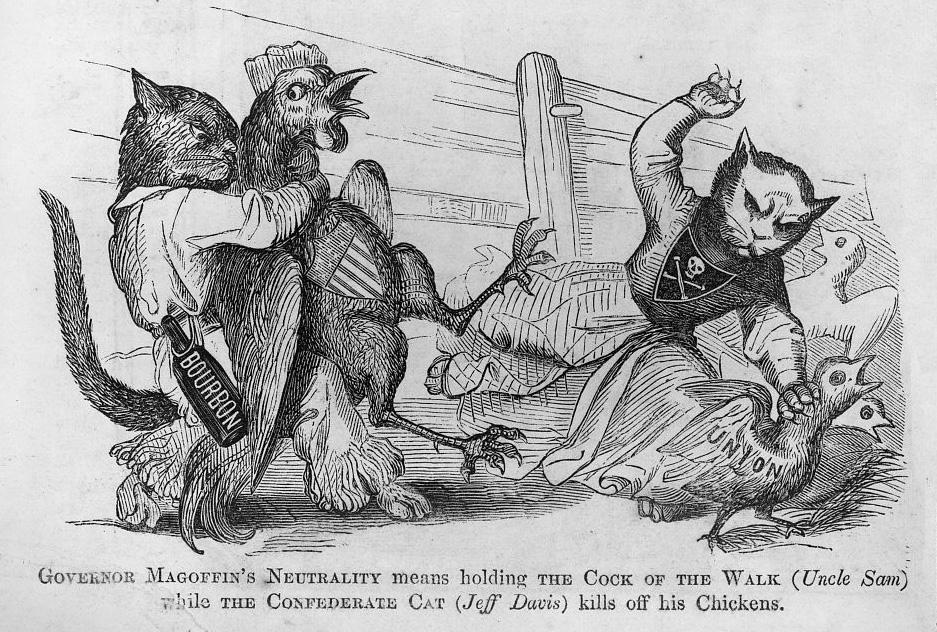

In 1861 when the Civil War erupted, the fact that the Busters were former southerners made life quite difficult for them. They did sympathize with the southern cause, but opposed slavery and had not supported Bell, the southern candidate, but had supported Stephen Douglas who also opposed slavery. The State of Missouri was divided along the imaginary Mason-Dixon line and the Buster home was near this line. Many of them felt safer in the Army than they would have felt at home. Neighbor was pitted against neighbor over the question of slavery. Their homes were under constant attack from marauding bands of raiders, cattle and horses were stolen and many times, their homes were burned. Many raiders, often raiders from Kansas, made life pretty unpleasant for them all over the northern part of Missouri. These marauding bands of thieves under the guise of soldiers, pilfered, robbed and intimidated the defenseless women and children of the men who were fighting for the southern cause. Some times houses were burned over the women’s heads, with little ones in their arms. These bands were of the lowest type, not brave enough to face real battles but did their warring on women and children.

The following story is told about grand-mother, Elizabeth Buster. “Quote” from Lottie Buster’s files.

Once when grandma was weaving homespun for her children’s winter clothing, one of these bands came, prowled around the barn and then came to the house. Not finding any “Rebels” around they took what they found loose. One man took out his knife and started to cut the wool from her loom. Grandma told him to stop because that wool was to be her children’s winter clothing, but he kept right on and paid no attention to her. Grandma reached for her dogwood stick, a heavy stick with which she poked up the fire with, and brought it down across his arm with all her strength. It broke his arm in two places. One of his comrades cocked his gun and shoved it against her breast and threatened to kill her, but the Captain, who knew grandma, ordered him to put down his gun. Then he said, “Aunt Betty, if you tell me what we want to know, where the things we are looking for can be found, I will protect you and your children.” Grandma had little choice in the matter, but her quick wit came to her side. “All right”, she said, “What do you want to know?” He replied, “We know that you have some valuable horses and saddles. If you will tell me where they are I will protect you, even with my life if need be.” “We know too that you know where they are.” “Yes” said grandma, “I know where they are and I will tell you if first you rid this house of your men and send them on about their business.” The Captain ordered his men to leave the house. Grandma looked him straight in the eye and said, “Those horses and saddles are in Price’s Regiment, in the Rebel Army, and my two sons are riding them. If you want them, go get them.” She had outwitted him but he kept his promise and departed with his men, without molesting her further. Some one later wrote a poem of the incident, one verse going like this:

The little old lady with the poking stick

Broke his arm in two places with one mighty lick

The brave soldier swore, and all was a fluster

This little old lady was “Aunt Betty Buster”.

One time during the Civil War, Grandpa Archibald was taken prisoner by a band of these marauding soldiers. He managed to escape from them and started to walk back home. In some way he had gotten hold of a Union coat. He was stopped once. “Who Goes there?” demanded the sentinel. Grandpa replied, “Captain Drydon”. “Pass on” said the sentinel and grandpa was safe because he was quick witted enough to give them their own Captains name.

|

| Civil War Guerilla Raider |

After a disastrous raid by Guerilla raiders, William Marion & Sam, the two older Buster boys, rode south to the Confederacy. It has been told that an aunt of theirs was killed by these raiders. She had a beautiful new rag rug on her floor, a very prized possession in those days. When the raiders began to tear up the rug, in search for a trap door which might lead to guns or other valuable possessions, the aunt protested and asked for time to pull out the tacks and take the rug up without ruining it. She was refused time, hit over the head with a gun butt and killed. A nephew, herding cattle near by was also killed. Rocks were tied around his neck and he was thrown into a pond to drown. All the cattle were stolen. (NOTE: My father, Albert M. Buster, son of William Marion Buster told this story many times, but we were not able later to verify who this aunt and nephew were. It is believed that they were relatives on Grandma Buster’s side of the family, Hendersons.) The Dave Henderson Jr. and George McDowell families had come to Missouri and Archibald from Tennessee, settling in Missouri, just cross the river from Fort Leavenworth the main trading post in that part of the country at that time. The Henderson and McDowell families later moving into Fort Leavenworth where many of them worked for the railroad later.

It is said that it was because of these dastardly acts by Guerilla raiders, that the Buster boys rode south to the Confederacy. We do not have any record of Sam’s service in the Confederacy but on the following pages, there is an account of William Marion’s service. In 1864, Archibald sold the farm and moved north to Nebraska City, Nebraska. Shortly after this move, Grandmother Elizabeth’s health began to fail. Also at this same time, the big muddy Missouri River began to flood an daughter Mary Jane and her baby were in danger of the flood waters. Archibald went to their aid, (Mary Jane’s husband, James Goodman, being away in the Army at that time.) Because of the rising flood waters, Archibald was not able to return home immediately. Grandmother Elizabeth became worse and died on March 1, 1865. It was thought that she had contracted Yellow Fever, so was buried at once, before Archibald could return home. She was buried at Wyuka Cemetery in Nebraska City. Some of Aunt Paulina Latham’s children are also buried near by.

Archibald was a school teacher, he taught a subscription school. Most of his wages were in corn, meat, potatoes, or whatever people could spare. School teachers were scarce and terms were short. School was only carried out in the winter time when there was little else to do. Archibald stayed on in Nebraska City after Elizabeth’s death where he made ox yokes and saddle trees. These his partner covered with rawhide and then sold them to freighters of the plains. Freighting from Nebraska City to Denver was a very thriving business before the coming of the railroads. Some of the Buster boys made good money driving ox teams and freighting long before they came of age. Thomas J. Hamilton, who married Sarah Elizabeth Buster, daughter of Archibald, was one of those freighters. He had three rigs, or wagons, pulled by oxen and hauled about five ton per rig. He made two trips to Denver in 1865 and one trip in 1866. They were getting ready to make another trip in 1866 when William Henry Hamilton, oldest son of Thomas and Elizabeth, was killed while herding cattle. All the cattle were stolen except one yoke of oxen belonging to James Goodman. As the story was told by Lottie: It seems the cattle were stolen by two men and two women and driven to Nebraska City for sale.

Among the cattle was a big white bull, easily recognizable. A friend or neighbor recognized these cattle and reported it to Thomas. This lead led to their capture and the two men were caught an executed. No report on what happened to the women.

After Archibald’s children were all married, he spent a great deal of his time traveling around and visiting amongst them. He used to travel from place to place driving a yoke of oxen hitched to a light wagon. His oxen were Duke and Dan and most always carried a homemade chair with a rawhide seat in his wagon. During the last years of his life, he quit traveling around so much and spent much of his time with his daughter Lizzie (Hamilton) north of Rockport on the farm. This time, when he did visit, he drove a little dark gray mare, Old Kitty, hitched to a single buggy. His visits were always short as he was anxious to return to the Hamilton farm. During the last years of his life, at abut age 89, he regained his eyesight and could read newspaper print without the aid of glasses. In the summertime you could often find him out north of the house, under the lilac trees, sitting in his little old fashioned rocker, reading his papers or his bible. He was deeply religious and well prepared for the day that was to come. In the wintertime, his favorite spot was near the west window of the house, reading and waiting for the call, which he knew would not be far off. A short description of Archibald, written by one who knew him goes like this: He had snowy white hair, dark blue eyes & heavy shaggy white eyebrows. He was a short stocky man. The Busters were a thrifty hard working clan with enough Irish in their blood to give them a keen sense of humor, quick wit, and a lovable disposition.

The call came for Archibald on April 22, 1894. He had taken a walk out to the barn to see his faithful old friend, “Old Kitty”. On his return he fell as he crossed the door sill coming into the house. A heart attack had put an end to his long and useful career. He was the oldest living man in Atchison County and one of it’s first settlers. He had served six weeks as a Justice of the Peace in Benton Township and after his first case, a particularly trying time, he filed his report and handed in his resignation, he had had enough of that. During this tenure he had performed several marriages and at least one inquest. He was laid to rest in the Hunter Cemetery, south of Rockport, Missouri.

Several other members of Archibald’s family have passed away in a similar manner, quite suddenly. His daughter, Mary Jane, on the evening of July 18, 1908 apparently in good health, ate her supper and suddenly became quite ill and passed away before a Doctor could be summoned Sarah Elizabeth passed away quite suddenly at the breakfast table on January 14, 1912. Claudius Green Buster ate his supper and then left the table to sit in his favorite rocking chair when he was stricken with a heart attack and died on the evening of May 12, 1918. On the morning of August 13, 1913, grand-daughter Martha Blevins arose to get breakfast, again in apparently good health. When her husband came in from doing chores he found her, partially dressed, but sitting in her chair dead.

_______________________________________________________

1996

Keith Davidson Buster

(1912-1997)

During the latter years of his life, Archibald lived with his daughter, Sarah Elizabeth Hailtonon the farm north of Rockport, Missouri.These times, when he did visit, he drove a little dark gray mare, named Old Kitty, hitched to a single buggy.His visits were always short now, and he was anxious to return to the farm. It is said that, at the age of 89, he regained his eyesight and could read the newspaper print without the aid of glasses. In his early nineties, he always boasted, and proved, that he could jump up in the air and crack his heels together three times before coming down. In the summertime, you could almost always find him out north of the house, under a lilac tree, sitting in his little old-fashioned rocking chair, reading his papers and Bible. He was a deeply religious man, having claimed to have read the Bible through nineteen times, and well-prepared for the day he knew was to come. In the wintertime, his favorite spot was near the west window of the house, reading and awaiting the call, which he knew could not be far off.

A short description of him, by one who knew him well, went like this: Archibald had snowy white hair, dark blue eyes, and very heavy white shaggy eyebrows; a short stocky man. He came from a hard-working clan; thrifty, but with enough Irish in his blood to give him a keen sense of humor, quick wit, and a lovable disposition. The call, for which he waited, came on April 22, 1894. He had taken a walk out to the barn to see his faithful "Old Kitty". On his return to the house he fell as he crossed the doorsill. A heart attack had put an end to his long and useful career. He had been the oldest living man in Atchison County, and one of its first settlers. He was laid to rest in the Hunter Cemetery at Rockport, Missouri.

Archibald had served six weeks as Justice of the Peace of Benton Township in Missouri. After his first case, a particularly trying one, he filed his reports and handed in his resignation. He said he had had enough of that. During his tenure, he had performed several marriages and at least one inquest.

One time during the Civil War, Archibald was taken prisoner by a band of the guerrillas, dressed as Uniion soldiers. Archibald managed to escape from them and started to walk back home. In some way, he had managed to secure a Union coat. He was stopped once; "Who goes there?" demanded the sentinel. Archibald replied "Captain Dryden". "Pass on" said the sentinel, and Archibald was safe because he was quick-witted enough to give them their own Captain's name, which he had remembered.

_______________________________________________________

1996

Keith Davidson Buster

(1912-1997)

During the latter years of his life, Archibald lived with his daughter, Sarah Elizabeth Hailtonon the farm north of Rockport, Missouri.These times, when he did visit, he drove a little dark gray mare, named Old Kitty, hitched to a single buggy.His visits were always short now, and he was anxious to return to the farm. It is said that, at the age of 89, he regained his eyesight and could read the newspaper print without the aid of glasses. In his early nineties, he always boasted, and proved, that he could jump up in the air and crack his heels together three times before coming down. In the summertime, you could almost always find him out north of the house, under a lilac tree, sitting in his little old-fashioned rocking chair, reading his papers and Bible. He was a deeply religious man, having claimed to have read the Bible through nineteen times, and well-prepared for the day he knew was to come. In the wintertime, his favorite spot was near the west window of the house, reading and awaiting the call, which he knew could not be far off.

A short description of him, by one who knew him well, went like this: Archibald had snowy white hair, dark blue eyes, and very heavy white shaggy eyebrows; a short stocky man. He came from a hard-working clan; thrifty, but with enough Irish in his blood to give him a keen sense of humor, quick wit, and a lovable disposition. The call, for which he waited, came on April 22, 1894. He had taken a walk out to the barn to see his faithful "Old Kitty". On his return to the house he fell as he crossed the doorsill. A heart attack had put an end to his long and useful career. He had been the oldest living man in Atchison County, and one of its first settlers. He was laid to rest in the Hunter Cemetery at Rockport, Missouri.

Archibald had served six weeks as Justice of the Peace of Benton Township in Missouri. After his first case, a particularly trying one, he filed his reports and handed in his resignation. He said he had had enough of that. During his tenure, he had performed several marriages and at least one inquest.

One time during the Civil War, Archibald was taken prisoner by a band of the guerrillas, dressed as Uniion soldiers. Archibald managed to escape from them and started to walk back home. In some way, he had managed to secure a Union coat. He was stopped once; "Who goes there?" demanded the sentinel. Archibald replied "Captain Dryden". "Pass on" said the sentinel, and Archibald was safe because he was quick-witted enough to give them their own Captain's name, which he had remembered.