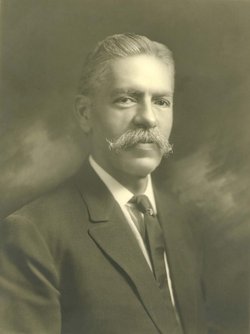

Buster's father worked in the mill industry, his connections opened an opportunity for her to meet someone like Félix Martínez; someone who definitely had been considered quite the catch. Handsome, gleaming a smooth and oblong face that sported a fashionable goatee like Paul Gauguin's, intensely dark eyes widen with wonderment and intelligence, honorable, and prominent while still exploring ambitions as tall as the Taos Mountains, Isaac and Virginia were easily smitten. Not only could Martínez trace his linage to colonial Spain, his ancestors living in the New World longer than the Busters, he also had two distinctive features that set him apart from the New Mexican Hispanic and pueblo community: one, he had light skin, and two, he acquired wealth quickly. In turn, the shy girl whose diamond face, hazel eyes, and thinly, stretched smile caught his attention. Her inexperience and innocence, tied to the mercantile industry that he and her father were a part of, solicited a match. Whether the pressure for Virginia to marry young was influenced by a blended household filled by a desire to escape from, especially being sent to a convent, or she was deemed of marriageable age, her wedding photo revealed uncertainty, and even a hint of sadness in her eyes, in spite of the lavish dress she was furnished in, promising her future of unimpaired wealth and prestige. The family story even revealed that the photographer told her to smile, that she was beautiful and had to smile. With a nine years difference between them, at least the gap was narrower than her parents, and especially her in-laws, reasonably forging a better match. They would have seven children, three daughters and four sons; and Virginia would be 31 with her last child.

Buster's father worked in the mill industry, his connections opened an opportunity for her to meet someone like Félix Martínez; someone who definitely had been considered quite the catch. Handsome, gleaming a smooth and oblong face that sported a fashionable goatee like Paul Gauguin's, intensely dark eyes widen with wonderment and intelligence, honorable, and prominent while still exploring ambitions as tall as the Taos Mountains, Isaac and Virginia were easily smitten. Not only could Martínez trace his linage to colonial Spain, his ancestors living in the New World longer than the Busters, he also had two distinctive features that set him apart from the New Mexican Hispanic and pueblo community: one, he had light skin, and two, he acquired wealth quickly. In turn, the shy girl whose diamond face, hazel eyes, and thinly, stretched smile caught his attention. Her inexperience and innocence, tied to the mercantile industry that he and her father were a part of, solicited a match. Whether the pressure for Virginia to marry young was influenced by a blended household filled by a desire to escape from, especially being sent to a convent, or she was deemed of marriageable age, her wedding photo revealed uncertainty, and even a hint of sadness in her eyes, in spite of the lavish dress she was furnished in, promising her future of unimpaired wealth and prestige. The family story even revealed that the photographer told her to smile, that she was beautiful and had to smile. With a nine years difference between them, at least the gap was narrower than her parents, and especially her in-laws, reasonably forging a better match. They would have seven children, three daughters and four sons; and Virginia would be 31 with her last child. Named after his father, Martínez was born in late March of 1857, the same month when the Dred Scot case ruled that Black Americans weren’t recognized as citizens and when John Breckinridge became vice president, (the one John David Buster of Kentucky’s 3rd Kentucky Infantry attempted to arrest Breckinridge for treason in 1861.) Despite that New Mexico had a low percentage of whites living in the territory, however since emerging to the U.S., all future governors were of Anglo descents appointed by each sitting president. The status of race ripened into separation of power, slowly undoing equal partnerships between Euro Americans and Mexican Americans at the seams, tearing completely by the 1920’s. The pueblo Indians, however, have always been considered at the bottom of the barrel; a misunderstood peoples that persists well into today, therefore, the notion of race has an acute history. Not only was Virginia’s mother and step-mother listed as “white” in the census, even though being of mixed heritages, Martínez and his family were listed as “white” as well.

The 1880’s revealed a rising concern in attitudes. An article written by Edmund F. Dunne, an American politician and jurist who served as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Arizona Territory, laid out his defense for people of New Mexico:

In your article yesterday on “The New Mexican Scandal,” … You are entirely mistaken in supposing that the people of New Mexico to whom you refer to as Indians with only about one-quarter admixture of white blood. The small contingent of Spanish blood mixed with the great body of native, producing only a mongrel race with all its vices and none of the virtues… That’s where you are wrong. The old Spanish settlers of New Mexico and their descendants have shown as much pride of race, as high regard for the purity of their blood as any other people that ever set foot on this continent.. You can go through New Mexico to-day and you will find that notwithstanding three hundred years of Spanish contact… the old families have preserved the genius Spanish type with remarkable purity… Go to New Mexico and mix… and you will find, not the little, black, weazened cut throat, murderous greaser type, mestizos, zambos, and outlaws… Having lived more than a year in New Mexico… I feel it my duty… to give my opinion, found on experience, as against yours…

In spite of his effects to sound conscientious and supportive, due notice that Dunne not only excluded the pueblo community entirely, emphasizing on the European connection, but also reinforced bigoted language. The Albuquerque Morning Democrat had argued again and again to have its people recognize as citizens, stating, “We do not hesitate to say that the Mexican population of this territory includes honorable, intelligent, refined and dignified gentlemen and ladies, and they should be accorded all the rights that pertain to citizenship.” It was a circumstance where the minority imposed distrust, and the main reason why it took over six decades for New Mexico to become part of the U.S. This type of prejudice would inspire Martínez to up his game.

The level of his success depended on both his ambitions and the color of his skin. Because his European ancestry made him appear lighter skinned than most, plus staying out of the sun by working his way up in the mercantile industry, his shrewd business mind and work ethics were not only recognized, but also rewarded. Starting out as a low level clerk, his business degree from St. Mary’s College improved his chances to climb-up the ladder as he continued studying business in Pueblo, and soon rose to partnership within less than a decade. His education opened him both Spanish and English; an ability to navigate in two cultures. The Busters more than likely crossed his path in Trinidad, Colorado just before he returned to El Mora, New Mexico and thus, continued the relationship by the time the Busters had also returned, a mere 30 miles between them. A year before his marriage, Martínez sold his partnership to establish his own, alongside of building a cattle business to compliment his wealth. The fire did not hinder his ability to reclaim his success, and neither did the expansion of the Santa Fe Railroad.

Martínez’s ambition outgrew commercialism. While his riches celebrated his reputation, he felt he had a higher calling: politics. In 1886 he was first elected at country treasurer, then Territorial House of Representatives two years later, all under a Democrat seat. New Mexicans of the Democrat persuasions tended to be the elite, in which, Martínez, surely was part of. Since becoming a territory, New Mexico experienced factions that essentially boiled down into two short-lived parties from the nuevomexicano elites: the Native majority and the wealthy Pro-American minority. The Hispanos longed to keep the status quo while the Pro-Americans longed for expansion, and aggressively pushed for modern land grants which overrode Spain’s and Mexico’s original land grants to the pueblo communities. The land grabs of New Mexico mirrored in the same practice as to what happened in Oklahoma.

Between Martínez’s real estate, timber, and cattle industries, these investments afforded him to purchase a newspaper out of Santa Fe called, La Voz del Pueblo, translation: “The Voice of the Community.” Relocating the publication to Las Vegas, he fulfilled both roles as president and editor. His motivation was to inform the community about the going-ons from within, (announcements, advertisements, etc.,) but, most importantly, his articles focused on many serious issues such land-grabbing of communal land owned by the Pueblo peoples, double standards within the law, wages gaps, and inequality of living standards between the Anglo-Americans and nuevomexicano. His moral obligations shifted into political ones. And people knew him, respectfully referring him as “Don Félix.” His children would refer him as “the Governor” not only due to his involvement in the community, but also because he was strict disciplinary, owning a specific tall, wooden chair he utilized for “the lecture chair”.

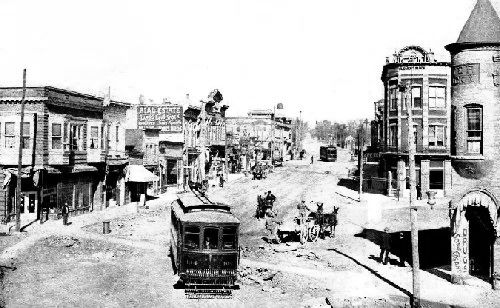

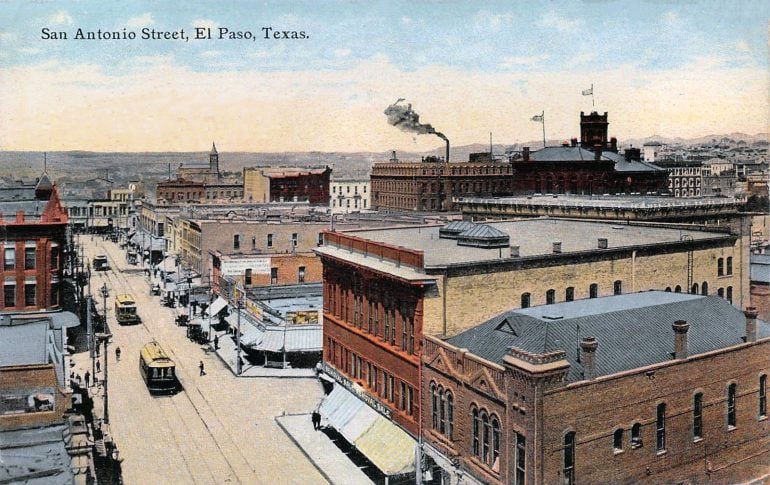

After finishing his four years as clerk of the U.S. and Territorial Courts for the 4th Judicial District, he had bigger plans than little Las Vegas. He met William Brian Jennings during the 1896 Democrat Convention in Chicago, and a year later, he and his family moved to 236 Tobin Place in El Paso, Texas.

He chose El Paso as another opportunity, perking his interest to help civilize the growing wild town as he had done so in Las Vegas. And it was no coincidence El Paso perked his interest. He remained close to his Mexican roots, sitting on the boarder of the U.S. and Mexico, to advocate harmony and equality between the two races. Martínez likewise had a keen sense that El Paso would grow much more quickly than Las Vegas, brought on by the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad and where the border town sat. He continued his habit of owning the local newspaper, El Paso Daily News, invested into real estate by opening El Paso Realty Co., co-organized the chamber of commerce, but then, took his roles a bit further: he purchased El Paso-Juárez Railway Co. while serving as several directors within the community, and doggedly assisted to facilitate a dam for irrigation from the Rio Grande and filter proper sewage for its citizens.

He ran for senator in 1912, and not surprisingly, he lost. The reasons weren’t necessarily tied to his political ideals, but rather to a somber truth: because he was of Mexican origin. Anglo Americans who held political power couldn’t conceive it, regarding him as a second class citizen in spite of his wealth. The first Mexican American to win the senate seat was Octaviano Ambrosio Larrazolo in 1928 from New Mexico. For Texas, it wouldn’t be until 1956 with Henry González, two years following the civil rights case, Hernandez v. Texas, which finally confirmed Mexican Americans as U.S. citizens and, thereby, having equal protection under the 14th Amendment. Another example the bigotry Martínez endured came down to purchasing a car. When he arrived at one of the only two automobile establishments in El Paso, he wasn’t too concerned about changing his work clothes after inspecting his irrigation on his ranch. He waited for the salesman to assist him, but during the wait, he was completely ignored. Martínez marched across the street to the other dealer where he purchased a Cadillac—fully in cash. That Cadillac owner, C.P. Henry, would later become his son-in-law, by the way. Martínez then drove to the first dealership to not only show the commission the dealer missed out, but also, to tell him off.

During this upheaval, Poncho Villa took advantage of the instability and often raided across the Mexican/ U.S. border to fund the on-going revolution. If the family story is true, then the mayor of El Paso requested if Martínez could establish a peaceful agreement with Poncho Villa and his militants from raiding the border town. He met the infamous bandit on the outskirts of Juárez where they exchanged pistols as a symbol of harmony. The Colt .38 revolver had remained with the family for quite some time; the grandson would eventually inherit it. Being the portraits and biographies of the progressive men of the West and Who's Who on the Pacific Coast supported Martínez’s 1911 peace attempt between Madera and Díaz, and since Villa supported Madera, it could have been a plausible family story. The revolution bled into El Paso in the spring of 1911, and that was why Martínez was called upon. But peace wouldn’t happen for another ten years, and so, as the fighting persisted, so did the raids.

The instability affected Martínez’s oldest daughter, Flora, the most. She married an employee of apothecary, essentially a pharmacist, Matias P. Hernández in 1898, one year after Klondike, Alaska in search of prosperity. In 1901, they moved to Juárez, Mexico, where Hernández worked for the Saminego drug store, and began a rather successful career. Hernández, being a member of city council, was marked for death in 1913. They crossed the border, leaving behind his property where Villa raided his store and slaughtered some of his horses for food. They took their three young sons, ages from one to eight years old. Unable to return to Mexico, Flora and Hernández moved on her father’s acreage in New Mexico to farm as a living. In 1919 they attempted to clean up the mess left behind, eventually relinquishing their properties while they were forced to rebuild their lives in El Paso.

Martínez’s dogged morality had rubbed many people the wrong way. He mobilized the platform of his newspaper as one method to shut down 162 saloons, cleaning up El Paso against gambling and prostitution. Often he would receive death threats which motivated him to carry a cane and a silver whistle. One family lore told a story of an attempted assassination, but specific details of how, where and when were absent and no other resources can be found to verify the story. Because he was a man of peace he never toted a gun around the town in spite of El Paso’s reputation. One of his peers described him as such:

At the end of his life, he assisted in establishing El Paso Public Library, what would become University of Texas, and the Elephant Butte Dam. Pneumonia took his life in March of 1916 when he was 58. On his death certificate, under “color or race,” he was listed as American, and his occupation as capitalist. Inarguably, he was the utmost influential Hispanic of his time. A building at the New Mexico Highlands University is named after him. Virginia would outlive him by 50 additional years, almost reaching to the age of a hundred, and watching the growth of El Paso change from the Six Shooter Capital to Sun City, and would produce the best Tex-Mex cuisine in the state.