We’re going to briefly revisit the practice of indentured bondage. Although the comparison of slavery and indentured bondage is far from being balanced, and not by any means equal to the experiences, there is no debate about that, however these two intuitions reveal an objectification about Western society: the misuse of labor under a Christianized nation.

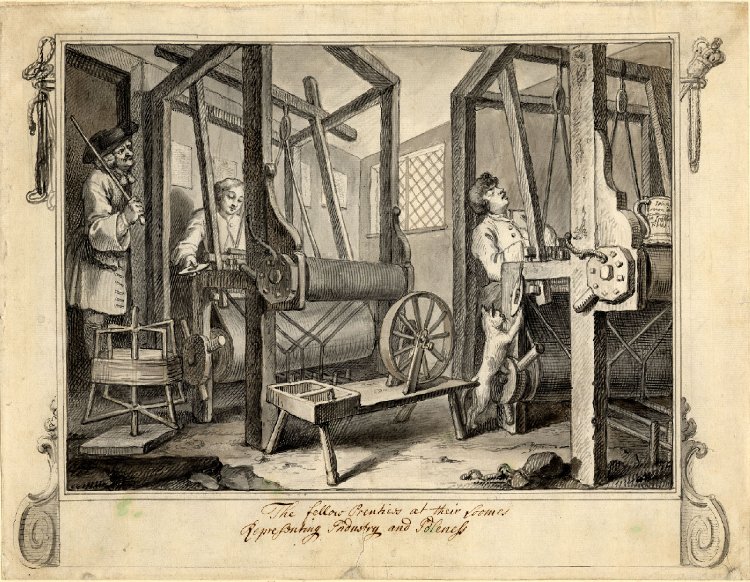

Five of William Buster/ Bustard's third great-grandsons were “indentured out” in 1844. This accepted procedure was also referred to as “binding out.” Trying to solve the problem of vagrancy with Anglo children started with the Tudors. During Henry the Eighth’s rein in 1535, poor children between the ages of five to fourteen, “may be put to service by the governors of the cities, towns, etc., to husbandry, or other crafts or labours…” In other words, they were forced into the positions of apprenticeships if they were caught stealing or begging, which could be a good thing, if they weren’t exploited and abused by those in charge. And just six years before indentured servitude became a thing, the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601 began the process of “binding out” for both adults and children, sparing with the rise and functionality of the workhouses as a means to fill in labor shortages while repositioning the poor. This Elizabethan law was designed to alleviate the financial burden of the poor within their local communities. Churches and justice of the peace were given the authority to decide who needed to be “bonded out” to tradesmen and husbandmen, to even extend this law into colonial Virginia, “to be brought up in some good and lawful calling. And whereas God Almighty, among many his other blessings, hath vouchsafed increase of children to this colony… who if instructed in good and lawful trades may much improve the honor and reputation of the country…”

Two hundred and forty-five years later, “binding” continued to be of use, so by the time Charles Woods Buster of Pulaski County, Kentucky died in 1841, his wife, Stacey Reynolds, was unintentionally placed in an awkward finical position with ten children. The mixed feelings of panic, dread, and melancholy surely overwhelmed her. She inherited her husband’s land, but had to use her children to harvest a meager living. After two years struggling to keep her family fed and together, the courts stepped in. John Milton age six, Charles Woods Jr. age ten, Henry Clinton age eleven, David Garrison age thirteen, and James Madison age sixteen, were “bound out” to neighbors until they were legally twenty-one when they could vote as responsible citizens. Charles and David went to the same family, under the patriarch of Alvin Jones, who already had five children of his own; and Henry and James went to the Muse brothers, an indication that the courts and neighbors were trying not to spread the Buster brothers too far away from each other and from their mother.

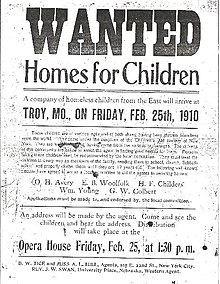

Now it’s unknown whether Stacey volunteered her five sons out of sheer desperation, or if these five were the most unruly out of the ten and the court deemed it necessary to interfere, but this transition from being “indentured” as a means to relocate into foster homes was the next transition from economical “binding” to genuine child welfare. In the document of Charles Woods Jr., a line “to treat in a humane and tender manner” was important enough to indicate a sincere concern for the well-being of children. The notion of foster care for orphan children had been around since the early Christian churches during the Roman era, placing orphans with widows, but it wasn’t until the early 1900’s in America when the government began to pay people for taking care of children in foster homes instead of being “bound out.” It’s also important to note that the five boys were taken care of well enough to at least live into their adulthood, and each to have even gotten married before pushing up daisies. John Milton lived the longest, remarkable at the age of ninety-six, and had moved westward to the harsh Nebraskan plains when he died during the height of the Great Depression in 1934. His mother, Stacey, did remarry to a James Gabriel Daulton in 1845, who was fifteen years her junior, and had six more children. The sting of being abandoned by both parents, whether by death or the court system, and remarriage with additional siblings, can only be imagined.

The intentions of “binding out” were twofold: One, to turn the poor into law abiding citizens who would not become a financial burden on society. And two, it provided free labor for the community, even if on a temporary basis. Before there was a foster care system that attempted to focus more on the protection and the welfare of children, for centuries children were considered as a viable workforce, alongside of adults. This procedure of “binding out” continued well into the 20th century, still under the implication of apprenticeship and with establishment of the orphan train phenomenon which transported inner city children to farmers so that they could learn a trade. The orphan trains officially ended in 1929 while child labor laws were put into effect in 1933.

No comments:

Post a Comment