|

| Elizabeth & William M. Buster |

The Rough and Tumble of Johnny Reb

Experience of 1861-1865. From the time he left his home, south of Rockport, MO until the close of his service in the Army. Became a POW for 2 years

First Missouri Calvary, C.S.A.

(1838-1923)

(1838-1923)

I left my home in Atchison County, Missouri near where Langdon now stands and started for Dixie Land under the leadership of John Thraikill. Our first stop was at Jim Gilkerson's somewhere north of the city of Fairfax now stands where we got our supper and our horses fed and then departed for parts unknown to me. We followed the bottom road to Mound City and arrived at a point somewhere on the Nodaway River sometime in the early hours of the morning and camped in the heavy brush along the stream. But secured our meals and horse feed from James Thraikill, an uncle of our leader. When darkness again shrouded the earth we mounted and left our friend and started on our way and came very near to coming upon a regiment from St. Joe. Had this happened, I am unable to say what would have occurred as our leader was a man who was never known to run from any fight. We passed five or six miles to the left of St. Joe and made our next stop between Platte City and Plattsberg, where we remained until darkness again fell around us. Then departed and rounded up, the next stop being at Memphis on the Missouri River, where we remained in the woods in hiding all day and crossed the river in a flat boat in the darkness of the night.

|

| Gen. Price |

After we had crossed the river, we began to think that the Kansas Jawhawkers were afraid of us so began to travel in the day time, and could see squads of men in the rear who did not seem over anxious to overtake us which they could have easily have done had they any desire to do so as our horses were pretty badly used up by this time. We traveled about as we pleased as we felt we were among friends and I guess we were as no one seemed to have any desire to cause us trouble. We at last arrived at Old Pap Price's headquarters on the Noosha River near Sedalia where the next morning where we pulled up stakes and departed for Springfield, Missouri, where we went into encampment for the winter and we had a good time with plenty to eat. (William officially enrolled in Springfield in December 25, 1861.)

In the Spring of 1862 the Yanks began to think they wanted a little blood-spilling and started a squad of Calvary toward Springfield. The came within fifteen or twenty miles of us one bright shiny morning when we were ordered to saddle our horses and mount, and away we went to meet them and held them in check until Pap Price could get his provisions and war supplied hold. We succeeded in holding them by resorting to skirmishes until we were ready to retreat to Springfield where we [sic] and marched to within one hundred yard of their lines which were formed in the neck of the prairie and fired a broadside at them. I never learned how many were killed, if any, but do not think there were any killed on our side, but our leader, John Tharikill, had a holster (Army pistol) shot from his hand and was disable a few days. We then fell back to Springfield where Gen. Price had his provisions and supplied packed and the Army then started on its march to Boston Mountains. Our regiment fell into the rear of the Army and was the rear guard during most of the march, a distance of about one hundred miles. I have since met one of the Yanks who followed us from Springfield, and many and funny are the stories they tell about capturing our supplies. But I tell them they never did capture any of our supplies as we were the rear guard most of the way and they never crowded us either.

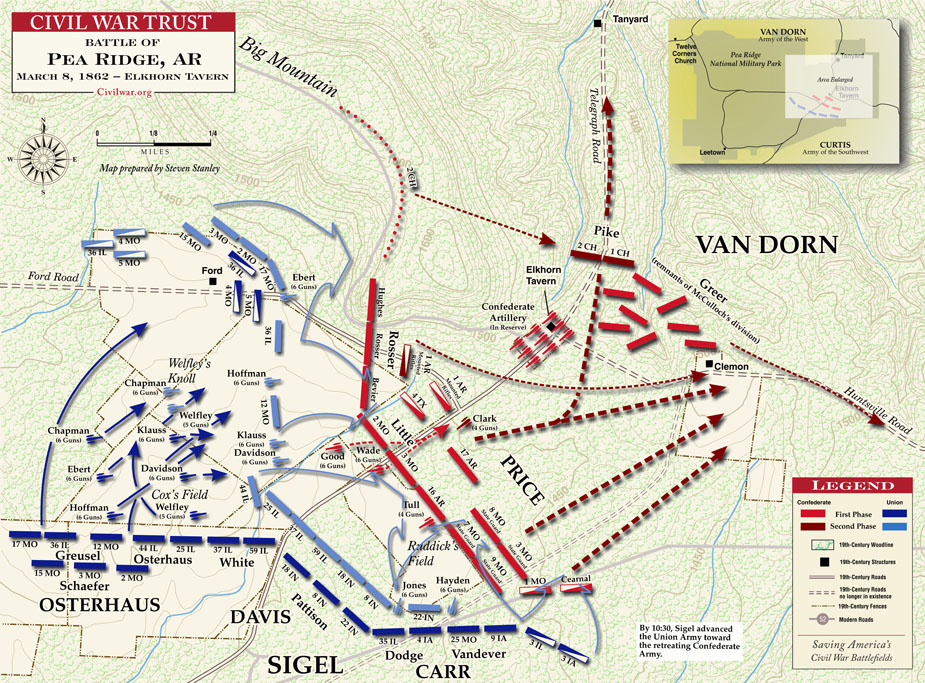

We remained at this camp without disturbance until a few days before the Battle of Elkhorn, when we were ordered to strike our tents and start north, the Yanks coming south, and we met [Franz] Siegel and Bentonville, Ark., who would fight a while and then fall back. We followed him until we got to the place where the battle Pea Ridge, Ark., was fought, where we were ordered to fallback, and I never knew why that order was given, unless it was because we had lost two commanding officers on our extreme left at the Battle of Pea Ridge. (Our regiment was on the right.) Siegel's Army would fall back every time we came up to them and they did not follow us as we fell back to Desark, Ark. During this march we never caught sight of a Yank, nor heard a gun fired. At Desark we were dismounted and our horses sent to Texas and we never saw them again, but we were paid for them. We were placed on a boat in the White River, the boat was almost as wide as the river and we wound up at Memphis, Tenn., where we remained about 2 weeks, then placed aboard (railroad) cars and sent to Corinth, Miss. It was the intention of our superiors to get us to Shiloh, but the battle of Shiloh was fought on the day we arrived at Corinth so we were unable to take part in the scrap.

We remained at Corinth, as I remember it, for a month or two, when the Federal troops began to advance on Corinth and were met by Confederate troops at Gun Town, north of Corinth. The part of the Army, to which I belonged, was marched out six to eight miles east of Corinth, then north, the intention being to come in behind the advance and cut off from the main Army and take them prisoners to Corinth, but the learned of our intentions and we only succeeded in exchanging a few shots with them as they retreated to the main Army. After which we went back to Corinth and got ready to evacuate, which we did in a week or two, and went south thirty to forty miles to Tupelo, where John Sharp Williams resides, where we remained two to three weeks. We then went on a raid to Hallow Springs, and from there to Iuka, taking everything we came to but the Federal troops, who could outrun any Johnny in the Command. At Iuka we got more army supplies than we knew what to do with for the time we had to stay, but we held the place for about a week and then succeeded in getting most of provisions away.

When [William Starke] Rosencrans came back we had one of the hardest fights we had ever been in, but succeeded in driving him back about half a mile, as had been our habit, but he refused to be driven further, so we lay on the battle field with the dead and dying between our lines, neither side being able to help them. But we finally got most of our men cared for as we did the driving back. our wounded were carried from the field of battle and were cared for, as were many of the Union soldiers who were wounded during the advance. Along towards morning Price began to take us out and we fell back to Iuka, while Price's Missiouians were left to bring up the rear. The Federals ran a battery up on a hill, about half mile from us, and opened fire, but they got high and hurt us very little. So we got started away at last and ran pretty lively about all day, they followed pretty lively too.

|

| Fort Robinette, Corinth, MS |

We arrived near Tupelo and rested for a week or two then started towards Memphis, and as the Union Commander was in the dark as to where we were going, Memphis, Bolivar, or Corinth, which were in a semicircle, we made a move as if going to Bolivar, where General [Edward] Ord was in command, but turned and went to Corinth where Gen. Rosencrans was in command of the Federal Troops. We took two lines of breastworks [temporary fortification made of wood and mud breast high, allowing soldiers to shoot in standing position,] when night came on and stopped the battle until 9 o'clock the next morning. When the signal gun boomed forth the command, away we went for the fray. Fort Robinette lay directly in front of us, and it being the best fortified place on the line, we took it and captured their cannon and we thought we had everything our way, but the division on our right failed to come up in time and we were forced to give up everything we had captured and fell back, it being far worse going back when it was coming up, we retreated over the very same ground that we had advanced over the day before.

|

| Gunboat 1861 |

When we got back to Hatchery River, Gen. Ord was there with his Army from Bolivar so after giving him a few rounds, Price took his Army thru the brush, down through the river and crossed on a hill-dam and got away from the Federals. We finally rounded up at Jackson, Miss., and were not bothered by the Federals for a long time. We lay back of Vicksburg, Mississippi all the winter of '62 and were there that the time the Gun-boats for for Vicksburg. We often went to Vicksburg and looked at [Ulysses S.] Grant's Army that lay just across the river in Millikan's Bend, where, in the spring of '63, Grant made his attempt to charge the course of the river which he failed. Sometime along about the first of April he pulled up stakes and started down the west side of the river to Bumont, or some such place, where he crossed over. We were ordered down on the east side of the river to try and stop him, but he succeeded in crossing. The Gun-boats succeeded in running past our batteries after a sharp fight, and one boat, on which Admiral Dewey of Manila fame [from the Spanish American War], was stationed was sunk. That was the place where he received his first lesson in warfare.

Another of the boats was disabled but they killed Captain [William] Wade of the Second Missouri Battle of the Confederate troops. The first place where we struck any of Grant's forces was at Port Gibson, where we had a sharp engagement, but he, being in command of plenty of men, was able to send a detachment around our flank. We fell back and skirmished with him all the way to Edwards Station, between Jackson and Vicksburg, where he flanked us again and then moved toward Raymond and captured the town, then marched to and captured Jackson, after which he turned towards Vicksburg. We again set part of his Army at Baker's Creek, of Champion Hill as some call it, where we fought him all day. But he kept sending his men, that were not engaged, around us, so we started to fall back about sundown and fell back to Black River and camped on the west side of the river until morning.

|

| Battle of Vicksburg |

During the engagement and retreat from Baker's Creek, Lt. Billy Hope of Co. E, Second Missouri Infantry, C.S.A., a Rockport boy, was wounded and, in the retreat, was carried on a litter for twenty-five miles into Vicksburg where he died pf his wounds. We were ordered back to the east side of the river the next morning to hold Grant in check until Pemberton could get everything into Vicksburg but we were unable to hold them for any length of time as they formed the line and charged us, capturing everything on the east side of the river. This was the 17th day of May 1863. The went right on and encircled Vicksburg, their lines extending from the river above to the river below the town. They charged two or three times in an effort to take the city by storm, but were repulsed every time with heavy loses. They finally decided to starve us out, which they did, and on the 4th day of July Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg and we, as prisoners, were then taken across the river to the place where Grant had quarters the winter before.

_(14759557101).jpg) |

| Confederate POW |

We were kept there for about a week and then put on a boat and started upriver for Cairo, where we put on (railroad) cars and went through Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, & Pennsylvania to Fort Delaware, below Philadelphia, where we were kept for about six months, with about half enough to eat, and from there we were taken to Point Lookout, Md., on the Chesapeake Bay, which was a very nice place and where we fared a little bit better. We remained there for about seven months, then being sent to [Elmira], NY., where we remained about eight months. At [Elmira] they concluded to exchange us. We were then, in February 1865, sent south to Richmond, Virginia, where we remained about a week.

On this trip we went thru North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, and on arriving at Mobile, had only time to shake hands with the boys and then ordered across the bay and try to hold A. J. Smith in check. He was advancing on Fort Blakeley. We had not been officially exchanged as of yet, but they came after us about the first of April and we were kept pretty busy, day and night, until the 9th day of April when they charged us and took us all in again. We had crossed the bay in a pretty lively skirmish. But this 9th of April was also the day Lee surrendered his forces to Grant, so the business part of the scrap was almost over. [The Battle of Blakeley was the final major battle of the Civil War, with surrender just hours after Grant had defeated Lee at Appomattox on the morning of April 9, 1865. African-American forces played a major role in the successful Union assault. Mobile, Alabama was the last major Confederate port to be captured by Union forces, on April 12, 1865. After the assassination of President Lincoln on April 15, 1865, other Confederate surrenders continued into May 1865.] After our capture, we were taken back over the battle field and formed in a hallow square, and so kept that first night, during which your humble servant walked out of the square and thought he was on the road to freedom again, when a Yank you possessed a pretty good pair of eyes succeeded in perusing me to return to the square and wait for daylight.

|

| Ship Island, Mississippi |

We were then sent to Ship Island, out in the Gulf of Mexico, where we were kept for two or three weeks, then placed onboard a Mississippi steamer and taken to New Orleans. While we were on Ship Island we carried the wood to do our cooking a distance of six miles, through sand six inched deep, and every guard was a nigger. Several of our boys were shot without any cause and we were at Ship Island when Lincoln was shot, which made matters worse than they otherwise would have been. The officers of the guard were white, and several of our officers, being with us, told them that if we were going to be shot down like dogs, then we would be all shot together. They, very soon, put a stop to the shooting.

On arriving at New Orleans we lay on board the boat all day and at night fall were started up the river. An Army friend and myself planned to make an escape, the only mean of so doing this was to jump overboard and swim to shore, which looked like jumping into a grave. About midnight we plunged, just behind the wheel of the boat, a side-wheeler, and swan to shore. Here we thought our troubles were over for we knew that most everything living around there were our friends. So we went out across the fields until we came to a swamp, which we waded around in until we made up our minds that we could not cross it, so my partner, and three others who had swam out after us, held council and decided to go to a farm house and get the landlord to pilot us across the swamp. We slipped up and found him out doing his chores and we made known our business. We were told by him that we had better give up for escape was impossible, the swamp being ten miles across and practicably impassable, that every place that could be crossed was heavily guarded by Union troops. But we refused his advice and wadded up river and made our way for about six miles when we were captured & put in jail for the night. The next day we were taken up river about ten miles and placed in a guardhouse with some of their own soldiers. We were treated well and everything was done for our comfort.

After two days we were put on a boat and sent up river towards Vicksburg where we heard that Johnson had surrendered our department. We were taken to Black River and given our parole, within half a mile of where we had been taken prisoner two years before. We were turned loose without money, clothes or food, and were hard pressed to guess What to do. But we learned here that if we were to take the oath, we could get transportation home. I told my partner that I thought this the best thing to do, but he declared that he would never do anything of the kind, so we parted company in the streets of Vicksburg and I have never seen or heard of him since.

I went up to Provost Marshall's office to take the oath and get my transportation, but he wanted me to put my name down as a deserter from the Confederate Army, which I refused to do, my friend was gone and I felt very much alone, but was not, as there was a lot of Confederate soldiers in town who were in the same condition as myself. They finally decided to give us transportation to the mouth of the White River, to get us out of town, and so we boarded the first boat that came up the river, but on arriving at White River, instead of getting off the boat, we hid on the lower deck and stayed there until we got to St. Louis, which was as far as the boat was going, so we were compelled to get another boat to bring us up the river.

We went aboard the Emma, which had a few crew of white men, hunted up the Captain, told him where we had been and the financial condition we were in, and promised to do anything that we could do for transportation. We were told to come aboard and finally arrived at Leavenworth sometime in the early part of the night. May of '65, where I thought I was all right, I had plenty of friends just across the river on the Missouri side. So I got up early the next morning and went down to the ferry to cross, but was told by the guard on the boat that I would have to get a pass before he would let me cross. I went to the Provost Marshall's office, told him where I had been and what I wanted, but could not get a pass without someone to vouch for me, but I had not been there for some time and knew no one in Leavenworth. I was up against it again, but a friend of mine on the Missouri side heard that I was on the boat and he came across as soon as he could get there and offered to get me a pass. But I declined to have him do so as I knew some horse robbers who lived over in Platte County, who were continually annoying returned Confederate soldiers, and I would not allow a friend to compromise himself by vouching for me under the circumstances. As the boat [sic] upriver from St. Louis was going to land at Weston, I again boarded it and landed on the Missouri shore and walked back to my friend's house, opposite Leavenworth. His name was R.B. Sissle. He died last fall, one of the heaviest landowners of the west.

In conclusion, I want to say that the Missouri Army never went into engagement, either against breastwork or a line of battle that the enemy was not compelled to fall back, except of Franklin, Tenn. where we went up against breastworks which we could not go over, but we stayed until the Union forces left, about midnight, and left us in possession.

I wrote this article at the request of my good friend, John G. Sutton, who, at the time I was thinking of joining the Army, strongly advised against such action, advising me that it was going to be a hard long fight and that I would face many hardships, and probably lose my life, and I never would have joined the Army had it not been for the fact that the part of Missouri from which I went to war was at that time overrun by a damnable set of robbers as ever run loose. [The Jawhakers.] Taking advantage of the squally conditions of the time to ply their depredations, and many were the dastardly acts that can be testified to by some of the older settlers of that community. So I entered the service and stayed until the "Battle of the Blakeley Sea," near Mobile, Alabama, in which it is claimed, the last cannons of the war were fired. I found that the advice, which I failed to heed was true, and many were the hardships endured by the boys on both sides who started out for a vacation of a few weeks, and to put a stop to the War of the Sixties.

retrieved from Ancestry.com, published Nov. 20, 2013